One of the main questions many land owners and fire managers often ask about prescribed burning is when is the best time of year to burn? This will vary depending upon specific land management goals. Timing will also depend upon when the burn can be accomplished safely and under favorable weather conditions. When planning prescribed burns it is important for fire managers to know and understand how many days are actually available during a specific season or over the entire year. Knowing this will allow fire managers to plan for and execute a predetermined number of burns during a given year. It can also aid in determining in which season or seasons it may be best to conduct their burns.

Limited Number of Burn Days

Most fire managers have several prescribed fires to conduct during a specific burn season, and if an adequate number of days are not available, some burns will not be conducted that year. Burns not conducted are usually postponed until the next year, adding more burns and needed burn days to an already limited schedule the following year. It can also drastically change management plans on that particular burn unit. More often than not, many burn units are not burned regularly or at all because of a limited number of burn days due to restricting burning during a traditional burn season. This can negatively impact resources in numerous ways, along with creating an increased work load and cost on fire managers trying to implement prescribed burns.

Because of the limited number of burn days, a fire manger may try to burn when conditions are marginal. This can result in a prescribed fire that is not as effective as it should be causing management goals to not be met. On the other hand, safety may be compromised when prescribed burns are performed under marginal or less than desired conditions because of the need to complete all of the planned burns during that traditional time frame. If prescribed fires were conducted year-round, then more days would be available for burning, and the most optimum days for achieving goals and safety could be used.

Weather Variables

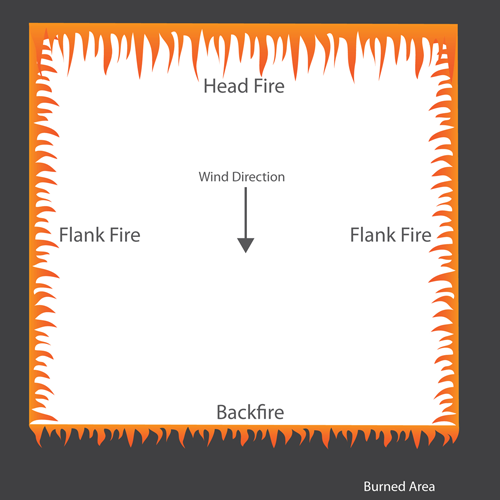

Weather has a major impact on prescribed fires and associated fire behavior. Therefore, the number of days available to burn each year is constrained by weather variables such as: temperature, wind speed, and relative humidity. Achieving the prescribed set of weather conditions during a particular time of the year has always been a dilemma faced by fire managers. If the goals of the prescribed burn are not extremely specific and safety concerns are maintained, then a wide range of conditions can be used for temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed. Often, a narrow window of weather parameters is required due to safety issues, policy, and regulation, which will reduce the number of available burn days.

Even if weather conditions can be met, timing of the prescribed burn is often limited to a single season by policy, tradition, or a lack of understanding of fire effects. Again, this limits the number of available days left to conduct prescribed burns. Remember that historically, fires occur throughout North America at any time of the year. Records show that fires set by Native Americans occurred in nearly all months, with a majority in the late summer. Also a majority of the lightning-caused fires in many regions of the United States occur during the growing season. In many areas burn season is late winter to early spring to correspond with green-up for livestock production, which also coincides with highly variable and changing weather conditions. However, conditions during the later winter can be favorable for wildfires which will further limit to the number of available burn days.

Limiting burning to a single season will continue to severely limit the application of prescribed fire in many areas. Also the lack understanding fire affects on native plant communities will also reduce the seasonal opportunities for conducting prescribed burns.

There are several publications and videos available that can assist fire managers to better understand fire prescriptions, fire effects and the best time to burn.

The Best Time of Year to Conduct Prescribed Burns http://pods.dasnr.okstate.edu/docushare/dsweb/Get/Document-7504/NREM-2885web.pdf

Fire Effects in Native Plant Communities http://pods.dasnr.okstate.edu/docushare/dsweb/Get/Document-2703/NREM-2877web.pdf

Fire Prescriptions for Native Plant Communities http://pods.dasnr.okstate.edu/docushare/dsweb/Get/Document-2704/NREM-2878web.pdf

The Impact of Fire on the Landscape SunupTV http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xh7_onVw8PQ&feature=plcp

Prescribed Burning for Pasture Management SunupTV http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jq0XAsWq8Ok&feature=plcp