Bison selecting post-fire regrowth (foreground) over dormant, unburned vegetation (background). Photograph by Stephen Winter.

Fire is a primary driver of many ecosystems, but is particularly important in the establishment and maintenance of grasslands and savannas. Numerous research studies have shown the effects and importance of fire on several grassland ecosystem properties, including plant productivity, plant species composition, nutrient cycling, and woody plant encroachment. Many North American grasslands support large grazing animals, either native wildlife (e.g., bison, elk) or introduced livestock. The role of grazing is also critical to the development and maintenance of grasslands, influencing many of the same processes as fire.

Though often considered independent, fire and grazing interact and influence one another. This is referred to as the fire-grazing interaction or pyric-herbivory (defined as grazing driven by fire). This interaction occurs when fires are present within a landscape or pasture allowing grazing animals to choose between burned and unburned areas. Due to high forage quality of post-fire regrowth, many animals are attracted to recently burned areas, including bison, cattle, elk, deer, sheep, and many others. Because of the differences in forage quality, grazing distribution is altered as animals heavily graze recently burned areas and avoid areas with greater time since fire. The preference for burned areas is very strong, and will often be greater than selection or avoidance of other features (e.g., water, topography, etc).

As fires move around the landscape or pasture, animals will follow to consume nutritious regrowth. This interaction between fire and grazing creates a mosaic or gradient of recently burned and grazed areas to areas with greater time since fire and no grazing. Across a landscape, the differences among such areas increase the number of plant and animal species (diversity), affects invasive species establishment, and nutrient cycling rates also vary with time since fire. Using the interaction of fire and grazing as a management tool can help conserve or restore ecosystem processes while maintaining livestock production.

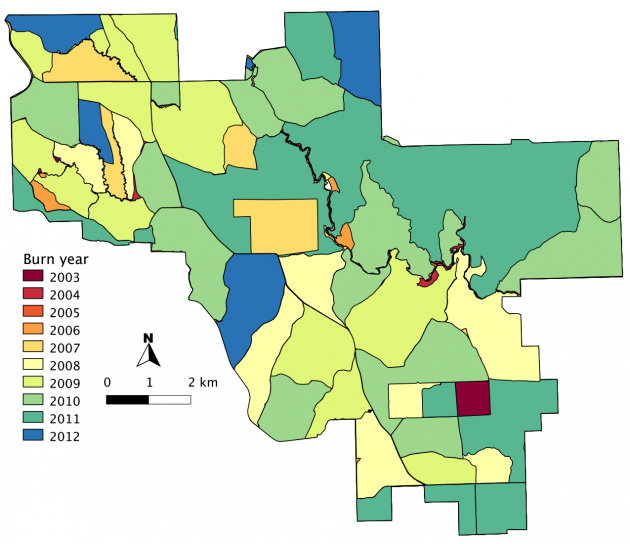

Patchy fire within the bison unit at the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in northcentral Oklahoma; there are no fixed burn units. The response of grazing animals to the patchy distribution creates the fire-grazing interaction.