Importance of Fire

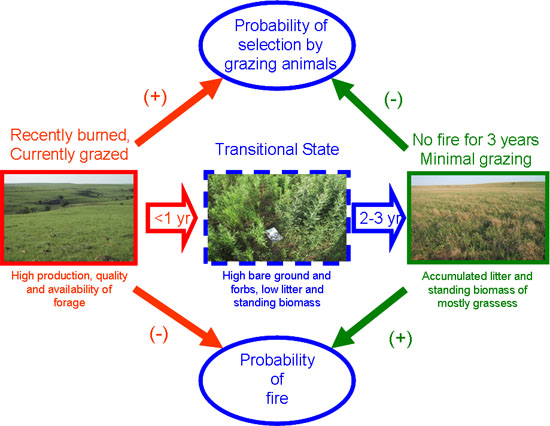

Fire is an important driver of many North American ecosystems, particularly grasslands. The influence of fire on the plant community is largely attributed to its removal of dead standing plant material, impact on forage quality, and the impact on grazing animals. Cattle production in undisturbed tallgrass prairie can be low due to the accumulation of dead standing plant material. However, fire can increase production over 75%. Historically, large bison herds followed fire as they were attracted to the lush regrowth that emerged. Today, managers use prescribed burning to capitalize on this change in forage quality for cattle production.

Forage Quality

Forage quality is typically expressed as crude protein (CP) which is based on the nitrogen content of forage. This nitrogen content is critical for microorganisms in the rumen. Other measures of forage quality include palatability (typically associated with texture and moisture content) and digestibility (largely based on fiber and lignin). The primary influence of fire on forage quality is the removal of standing, dormant plant material. Forage quality is largely a function of time: as plants age (mature) they decrease in quality. This decrease in quality is due to the increase in fiber and lignin content, resulting in reduced digestibility and animal consumption. Prescribed fire remove dormant plant material, increasing the nutrition and digestibility of post-fire regrowth. While prescribed fires are commonly conducted during the late winter or early spring, growing season (summer) fires have the same effect and can boost forage quality during a period of the year where it is typically decreasing. Furthermore, the interaction of fire and grazing will impact below ground plant growth by increasing nitrogen mineralization and plant nitrogen availability, and improving the root tissue quality.

Benefits of Higher Forage Quality

Forage quality is a critical component of cattle production including reproductive efficiency, rebreeding, calf production, animal growth and milk production. Understanding the importance of fire to native rangeland plants and the potential benefits to cattle can be a useful tool for ranch managers.