Regional fire consortia serve as a link between regional stakeholders, managers, practitioners, and scientists. The consortia are funded through the Joint Fire Science Program (JFSP), a federally funded program designed to address the emerging fire science needs of policymakers and fire managers.

As a part of their mission, the JFSP has invested significant resources into science delivery. Specifically, JFSP has established 14 regional fire consortia to promote fire science acess to managers and to support communication between managers and researchers. The program adopted a regional approach to fire science delivery because research and information needs vary across the nation. Collectively, the consortia represent a collaborative effort, but each group works independently of one another to focus on the specific needs of their region. The consortia promote fire science distribution through many different methods including: creating websites, publishing newsletters, sponsoring conferences, organizing field days, sponsoring webinars, and through social media (Facebook and Twitter). The 14 regional consortia are: Alaska, Appalachians, California, Great Basin, Great Plains, Lake States, Oak Woodlands, Northern Rockies, Northwest, Pacific, South, Southern Rockies, Southwest, and Tallgrass (see figure below). Below is a summary(and link) to each of the 14 regional consortia, synopsis was taken from the website of each consortia.

The primary purpose of the Alaska Fire Science Consortium is to strengthen the link between managers and scientists, providing an organized fire science delivery platform, and facilitating collaborative scientist-manager research development.

The primary objective of the Consortium of Appalachian Fire Managers and Scientists (CAFMS) is to form a widening network of fire managers and scientists to facilitate knowledge exchange among managers and scientists. CAFMS includes fire managers along with goverment and university scientists throught the Appalachian region which stretches from Pennsylvania to Alabama.

The primary goals of the California Fire Science Consortium are: 1) To become a clearinghouse for fire science resources in California, and 2) To encourage collaboration between fire researchers, land managers, and other stakeholders.

The goals of the Great Basin Fire Science Delivery Project are: 1) Provide a forum where Great Basin land managers can identify technical needs with respect to fire, fuels, and post-fire vegetation management, 2) Develop/synthesize the necessary information and technical tools to meet these needs, and 3) Provide the necessary information and tools through venues most preferred by field staff, field office managers, and higher administrative levels.

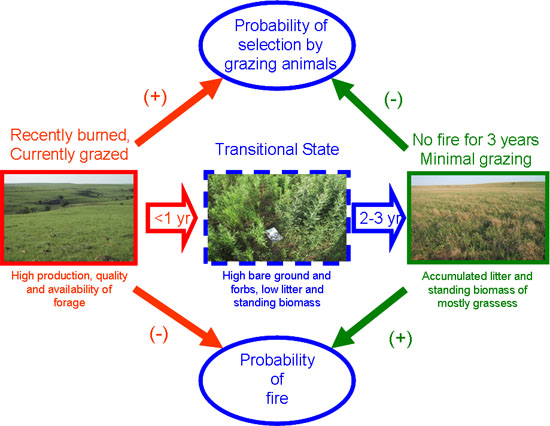

The Great Plains Fire Science Exchange is a network of landowners, managers, practitioners, and scientists interested in the fire-dependent grassland ecosystems of the Great Plains region. Their mission to assist land managers and the fire community to make sound decisions based on the best possible information.

The Great Plains Fire Science Exchange is a network of landowners, managers, practitioners, and scientists interested in the fire-dependent grassland ecosystems of the Great Plains region. Their mission to assist land managers and the fire community to make sound decisions based on the best possible information.

.

The mission of the Lake States Fire Science Consortium is to accelerate the awareness, understanding, and adoption of wildland fire science information by federal, tribal, state, local, and private stakeholders across the Lake States from Minnesota to New York, and the adjacent Canadian provinces of Ontario and Manitoba. This Consortium aims to link managers, scientists, policymakers, and disciplines by providing information and tools to support management of fire-dependent ecosystems in the Lake States region.

The mission of the Oak Woodlands and Forests Fire Consortium is to provide fire science information to resource managers, landowners, and the public about the use, application, and effects of fire. Fire science dissemination efforts include workshops, symposiums, newsletters, and literature syntheses focusing on topics identified by regional fire practitioners as areas needing credible and accessible science information.

The Northern Rockies Fire Science Network seeks to enhance communication between managers and scientists about fire management issues and research products. The Northern Rockies Fire Science Network aims to facilitate interactions between managers and scientists; identify fire and research needs; and improve access to knowledge and tools to serve those needs.

The Northwest Fire Science Consortium seeks to provide: 1) A delivery system for the effective dissemination and adoption of fire science information, knowledge, tools, and expertise; 2) A framework within which a variety of existing organizations and outreach programs focused on fire science delivery can coordinate more effectively; and 3) A venue to increase researcher understanding of the fire science needs of practitioners.

The Pacific Fire Exchange represents Hawaii and the U.S. affiliated islands in the Pacific. Their vision is a reduced threat to ecosystems and communities in the Pacific from wildfire. Their mission is to facilitate fire knowledge exchange and enable collaborative relationships among Pacific stakeholders including resource managers, fire responders, researchers, landowners, and communities.

The Southern Fire Exchange represents 11 southern states and is building on the long history of fire science deliver and outreach that already exists in the South. Their mission is to increase the availability and application of fire science information for natural resource management and to serve as a conduit for fire managers to share new research needs with the research community.

The Southern Rockies Fire Science Network is user driven, which means scientists and those who use and benefit from science will work together to answer important questions through collaboration that involves face-to-face communications and use of technology. Through such tools as workshops, field trips, webinars and web-based communication, collaborative processes can draw together disparate research and resource-management cultures to address complex wildland fire issues.

The Southwest Fire Science Consortium is a way for managers, scientists, and policy makers to more effectively interact and share science. The Southwest is one of the most fire-dominated regions of the US, but limited in terms of organizations focused on fire research and information dissemination. In the Southwest there are many localized efforts to develop scientific information and to disseminate that to practitioners on the ground, but these initiatives are often not well coordinated or aware of all the information and resources that are available. The real need for a consortium is to help bring these parallel efforts together to be more efficient and inclusive.

The Tallgrass Prairie and Oak Savanna Fire Science Consortium is comprised of fire practitioners, scientist, outreach and extension specialists, volunteers, educators and enthusiasts from the region. They are dedicated to fire science outreach through webinars, discussions, and field trips all to foster fire knowledge sharing.

Planning to use prescribed fire starts with determining what the land management objectives are and deciding if prescribed fire will help achieve the objectives. This process can take some time, but it is very important for determining where, when, and how prescribed fire can be used. Once it is determined that prescribed fire is an appropriate tool to meet the objectives, then a prescribed fire plan should be prepared. The prescribed fire plan is a document that describes the area to be treated with fire, the prescribed fire objectives, and a plan that includes a combination of prescribed fire ignition techniques, season of burn, and weather conditions to meet the defined objectives. Setting the objectives of the prescribed fire is a very important step in prescribed fire use.

Planning to use prescribed fire starts with determining what the land management objectives are and deciding if prescribed fire will help achieve the objectives. This process can take some time, but it is very important for determining where, when, and how prescribed fire can be used. Once it is determined that prescribed fire is an appropriate tool to meet the objectives, then a prescribed fire plan should be prepared. The prescribed fire plan is a document that describes the area to be treated with fire, the prescribed fire objectives, and a plan that includes a combination of prescribed fire ignition techniques, season of burn, and weather conditions to meet the defined objectives. Setting the objectives of the prescribed fire is a very important step in prescribed fire use.